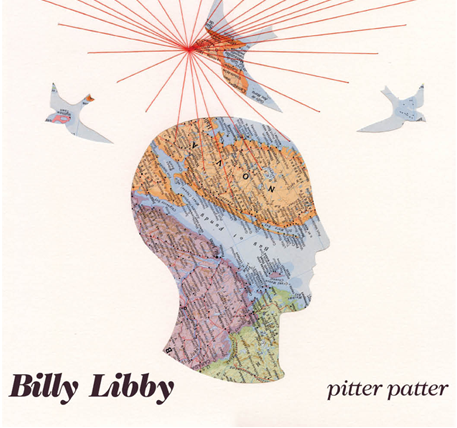

SOUND: Billy Libby "Pitter Patter" EP

For those of you missed our Exit Strata: Print! No. #1 launch party, you also missed out on a rare acoustic session by singer/songwriter Billy Libby (although thankfully you can check out a video clip of the performance here).

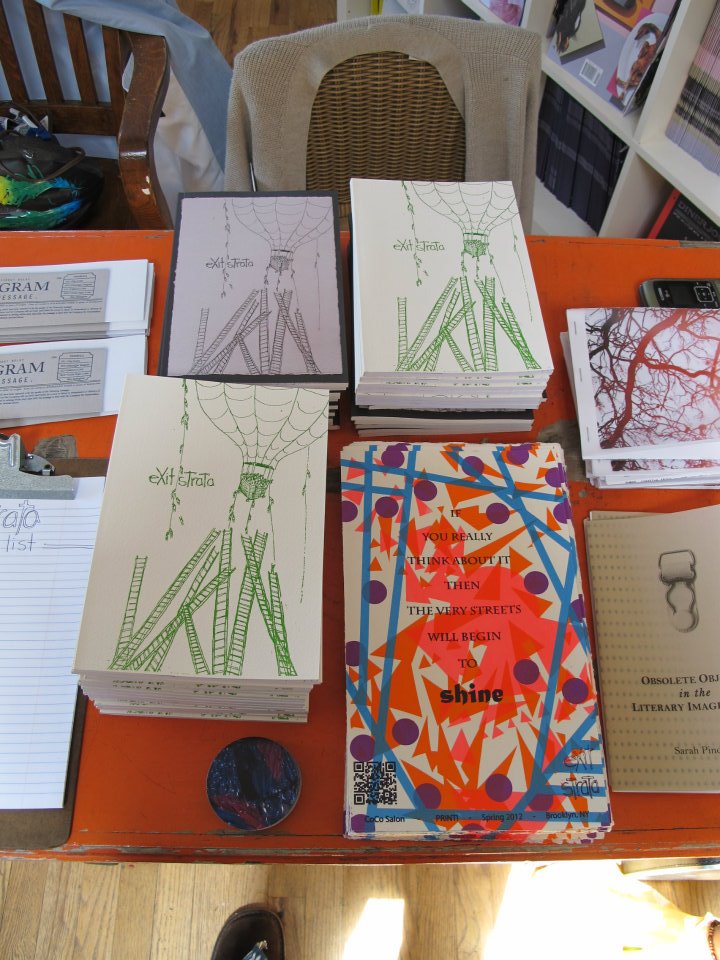

Taking Stock/In Stock :: Editorial Updates AND at a Bookstore Near You

[caption id="attachment_1414" align="alignleft" width="504"] clockwise from top left: Exit Strata PRINT! vol. 1 "brownie", PRINT! vol. 1 limited edition, blood atlas (DeSilva-Johnson), obsolete objects in the literary imagination (Pinder), limited edition vol.1 broadside[/caption]

You know how, just when you think that everything is about to slow down, and you're going to have time for all the things on your To-Do-list, which is looking more and more like an epic poem? And then, you know, it doesn't slow down at all?

Yeah. Then.

Well, that's kind of how it's been since the print launch...

clockwise from top left: Exit Strata PRINT! vol. 1 "brownie", PRINT! vol. 1 limited edition, blood atlas (DeSilva-Johnson), obsolete objects in the literary imagination (Pinder), limited edition vol.1 broadside[/caption]

You know how, just when you think that everything is about to slow down, and you're going to have time for all the things on your To-Do-list, which is looking more and more like an epic poem? And then, you know, it doesn't slow down at all?

Yeah. Then.

Well, that's kind of how it's been since the print launch...

FILM: ornana

A month ago, I left New York—drove from Brooklyn sixteen hours straight to Peachtree City, Georgia. When I pulled up, a few of my favorite people were on the back porch of a normally quiet suburban house. We were gathered to film another ornana short.

FIELDNOTES: Jacob Perkins : From the Cannery, pt 1

Field Notes: From the Inlet

EDITORIAL :: NEW SERIES ANNOUNCEMENT: "FIELD NOTES"

"None of us can ever retrieve that innocence before all theory when art knew no need to justify itself, when one did not ask of a work of art what it said because one knew (or thought one knew) what it did.

From now to the end of consciousness, we are stuck with the task of defending art. We can only quarrel with one or another means of defense."

- Susan Sontag, Against Interpretation

“...writing can't be a way of life - the important part of writing is living. You have to live in such a way that your writing emerges from it.” ― Doris Lessing

"None of us can ever retrieve that innocence before all theory when art knew no need to justify itself, when one did not ask of a work of art what it said because one knew (or thought one knew) what it did.

From now to the end of consciousness, we are stuck with the task of defending art. We can only quarrel with one or another means of defense."

- Susan Sontag, Against Interpretation

“...writing can't be a way of life - the important part of writing is living. You have to live in such a way that your writing emerges from it.” ― Doris Lessing

HELIOPOLIS PRESENTS: Steven Rose and Joanna Seitz

The AWESOME CREATORS at Heliopolis Project Proudly Present: STEVEN ROSE AND JOANNA SEITZ OPENING: June 1st, 2012, 7-10 pm VIDEO SCREENINGS: June 6, 13, 20 at 9pm Heliopolis 154 Huron St. Brooklyn, NY 11222 suncityprojectspace@gmail.com “Come; let us squeeze hands all round; nay, let us all squeeze ourselves into each other; let

SOUND/STAGE: Song from the Uproar

SONG FROM THE UPROAR is a "multimedia chamber opera" ...and is like nothing you've ever seen. Marrying intensely rigorous avant classical music from the visionary new composer Missy Mazzoli, with the filmic, aesthetic vision of Stephen Taylor, SONG FROM THE UPROAR is a personal, ecstatic, and immersive response to the life of Isabelle Eberhardt (1877-1904)-- an inspiring and little known tale in which the show's creators found "vibrant and relevant" parallels to their own: to the universal struggles for love and self-discovery in which we all take part.

FILM: My Heart is an Idiot – Douglas Wright

I'm always excited whenever Portland filmmaker David Meiklejohn releases a new project out into the world. He's a multi-talented writer, director, poet, and storyteller (his short story Gardens is featured in Exit Strata: Print! No. #1). We've have known each

AWESOME CREATOR: Peter Jay Shippy, Poet/Educator

Amid all the excitement around Exit Strata’s Print! Launch, I have been thinking about the previous launchings that have brought me to this project. One of the most important launches for me was being set off on my journey into

POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 30! (Could it be?) :: Lindsey Boldt on Aimé Césaire

The other night poets Julian Brolaski and E. Tracy Grinnell were in town and in a bar rotten with poets in North beach, we got to talking about translation and our varying positions on the desire vs. intimidation spectrum in relation to doing our own translations. I brought up the Martinican poet, Aimé Césaire, as an example of a poet whose writing would interest me enough to translate it. I had been saying how French can feel too precise, too clean, too “le mot juste” when I really love a hot mess. Aimé Césaire takes French, a very coy language, very good at hiding its skeletons, and busts open the closets letting the nasty flesh-dripping zombies come out...and muck things up. Césaire’s French, one that excretes vivacity, vitriol and jouissance like the flora and fauna, the active volcanoes he invokes in his poems, reminds us of the proliferation of Frenches, just like our current proliferation of Englishes, that exist in spite of and because of France’s imperialist history.

Julian brought up the hybridity of Cesaire’s texts, specifically thinking of his “Cahier d’un retour au pays natal” [Notebook of a return to the native land] which reminded me of my first encounters with Césaire in college. I had never seen prose live and move like his--be that “free”. I had been trying to wake my own prose writing from a death-like stupor when a professor of French and Francophone literature, Maryanne Bailey, who had visited Césaire in Martinique, introduced us to his collected poetry, translated by Clayton Eshleman. We read it both in French and English and I learned in the process that if you want your writing to live on the page it really helps if you hate the language, hate its restrictions and biases. You have to be willing to beat it up and knock it around a bit. You have to let your true ambivalence show. No, more than that, you have to make the language speak your radical visions; the same ones that would tear apart and rip out at the roots the society that grew that language and the shit storm you grew up in. As Césaire says in his essay “The Responsibility of the Artist” when referring to decolonization,“What is necessary is to destroy it, that is, tear out its roots. This is why true decolonization will either be revolutionary or will not exist.” [ed: full text at link]

The other night poets Julian Brolaski and E. Tracy Grinnell were in town and in a bar rotten with poets in North beach, we got to talking about translation and our varying positions on the desire vs. intimidation spectrum in relation to doing our own translations. I brought up the Martinican poet, Aimé Césaire, as an example of a poet whose writing would interest me enough to translate it. I had been saying how French can feel too precise, too clean, too “le mot juste” when I really love a hot mess. Aimé Césaire takes French, a very coy language, very good at hiding its skeletons, and busts open the closets letting the nasty flesh-dripping zombies come out...and muck things up. Césaire’s French, one that excretes vivacity, vitriol and jouissance like the flora and fauna, the active volcanoes he invokes in his poems, reminds us of the proliferation of Frenches, just like our current proliferation of Englishes, that exist in spite of and because of France’s imperialist history.

Julian brought up the hybridity of Cesaire’s texts, specifically thinking of his “Cahier d’un retour au pays natal” [Notebook of a return to the native land] which reminded me of my first encounters with Césaire in college. I had never seen prose live and move like his--be that “free”. I had been trying to wake my own prose writing from a death-like stupor when a professor of French and Francophone literature, Maryanne Bailey, who had visited Césaire in Martinique, introduced us to his collected poetry, translated by Clayton Eshleman. We read it both in French and English and I learned in the process that if you want your writing to live on the page it really helps if you hate the language, hate its restrictions and biases. You have to be willing to beat it up and knock it around a bit. You have to let your true ambivalence show. No, more than that, you have to make the language speak your radical visions; the same ones that would tear apart and rip out at the roots the society that grew that language and the shit storm you grew up in. As Césaire says in his essay “The Responsibility of the Artist” when referring to decolonization,“What is necessary is to destroy it, that is, tear out its roots. This is why true decolonization will either be revolutionary or will not exist.” [ed: full text at link]