[re:con]versations :: OF SYSTEMS OF :: digging deeper with CYCLORAMA's Davy Knittle

[line]

[box]

[quote]In April 2015, The Operating System’s 3rd Annual 4-Chapbook Series, OF SYSTEMS OF, appeared on the scene. A strikingly beautiful set, featuring original art created for the series by Emma Steinkraus, these slim volumes in fact contain multitudes — and their diverse, stylistically varied voices represent four new, decidedly distinct entries into the seemingly ever expanding landscape of young poets publishing today.

In celebration and anticipation of our launch reading this week at VON I wanted to dig deeper with these poets, giving them an opportunity to engage in process dialogue about these texts and their creative practice, and giving you the opportunity to break right through that fourth wall.

I stole a line (which is to say, I recycled some of my own questions) from an interview I did with poet JP Howard, which appears in SAY/MIRROR — and extrapolated from there in speaking to each of these poets, teasing out answers as different as the poets themselves.

Please consider this template, approaching The OS’s key concerns of personal and professional practice/process analysis combined with questions of social and cultural responsibility, as an Open Source document — questions to ask yourselves or others about process and the role of poetry today.

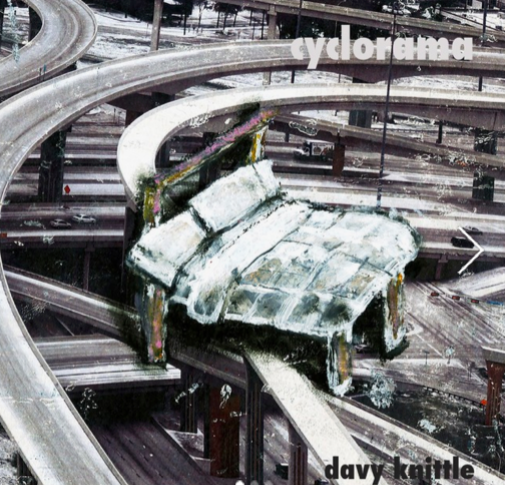

In this conversation, I talk to Davy Knittle about his work and his debut chapbook on The OS Press, Cyclorama.

Series Editor / OS Managing Editor Lynne DeSilva-Johnson [/quote]

[/box]

[line][line]

[articlequote]My poems finally feel like they want to talk to one another. They’re interested in process, and in movement around urban public space as a kind of process. Every point in a city feels like it’s charged with itself because it’s both separate from all other points, and yet it exists because of them. If the poems in cyclorama are working to model some of the exciting precariousness of being both in a private world and in a public space (like a park, a street, a subway platform, etc.) then each of the poems is also kind of a starting over. Each poem in the collection is an opportunity to try again, to pick up at the last poem’s limits. – Davy Knittle [/articlequote]

[line][line]

Who are you?

I’m Davy. I’m torn here between giving contextual information and giving emotional information. I live in Iowa City, but I’m in the process of moving to Philadelphia, where I’m from, and the city that has my heart.

Why are you a poet?

If I’m a poet, I’m a poet because I write poems, and because the kinds of community that matter to me the most are those that form around poetry. I’m a poet because making space for the kinds of conversations that can be occasioned by poetry are important to me. A lot of the communities I’ve been a part of where poems are the common language are communities of young people, usually high school students. For the past two years, I’ve run a poetry club at Tate High School in Iowa City, and often I feel like I keep writing poems because I’m amazed at the way a poem can be a living heart, and can make it a little easier or more pleasurable or both to be a person, and be in a body, when those things feel difficult.

I ran a reading series this past year with my partner, Sophia Dahlin, and having readings in our house in Iowa City was an excellent reminder of how close other people feel to me at a reading, and how a room feels like a community in ways that remind me of why I wanted to be a Unitarian Universalist minster as a kid – to bring people together in a way that aspires to make space for all of their humanness, to make a room that can hold what’s in everyone’s heart.

When did you decide you were a poet (and/or: do you feel comfortable calling yourself a poet, what other titles or affiliations do you prefer/feel are more accurate)?

It’s not that I feel uncomfortable with “poet” as a way to refer to myself. It’s more that I’m curious about having a noun to refer to a procedure. I’m a person who writes poems.

[line]

What’s a “poet”, anyway?

A person for whom a part of their life happens within the space of poems, and who is interested in observation as a mode of living.

What is the role of the poet today?

To be attentive. I taught an undergraduate poetry course this year at Iowa and referred to it regularly as a course in observation. Being a poet, for me, means paying attention to what’s visible and invisible and how the disparate features of things work together or fail to work together.

What do you see as your cultural and social role (in the poetry community and beyond)?

I’m torn here, too, between thinking about what poets do and what I do. Sophie and I ran a reading series this year in Iowa City called the Human Body Series, and the series made me feel that my role was to bring poets I loved into the room where folks new to their work could hear them. I think my role, and maybe everyone’s role, is to keep participating. To show up at readings. To keep writing. To tell someone when you love their work and why you love it. Beyond: I don’t know. It’s important to me to help folks in my life who are scared of poems to find a way in, to figure out a mode of thinking about poems (or just one poem) that’s exciting or interesting to them. Sometimes that happens in the classroom. Sometimes in other places. I went with my mom to her knitting group in April and spent a long time talking to one woman about why she found poems scary, and why she found them exciting. That was a pleasure.

[line]

Talk about the process or instinct to move these poems (or your work in general) as independent entities into a body of work. How and why did this happen? Have you had this intention for a while? What encouraged and/or confounded this (or a book, in general) coming together? Was it a struggle?

My poems finally feel like they want to talk to one another. They’re interested in process, and in movement around urban public space as a kind of process. Every point in a city feels like it’s charged with itself because it’s both separate from all other points, and yet it exists because of them. If the poems in cyclorama are working to model some of the exciting precariousness of being both in a private world and in a public space (like a park, a street, a subway platform, etc.) then each of the poems is also kind of a starting over. Each poem in the collection is an opportunity to try again, to pick up at the last poem’s limits.

Did you envision this collection as a collection or understand your process as writing specifically around a theme while the poems themselves were being written? How or how not?

I envision cyclorama as the best models of that kind of precarious movement through city spaces of a much larger body of work. I throw out just tons of work. The poems in cyclorama do some of the things I want my poems to do, and work together in some of the ways I want my poems to work together. They’re kind of a model city, in the way that model city is an attempt at something bigger: contained unto it self and yet representing the desire to exist in a different sphere.

[line][line]

[articlequote]The poems in cyclorama are interested in what kinds of participation are possible in the public sphere, and what kinds of fear or excitement motivates or makes possible different modes of participation for different folks. For whom is the public sphere public? Who has the power to change the kinds of participation that are possible for different people and groups at different times? – Davy Knittle [/articlequote]

[line][line]

The four chapbook collection lives under the umbrella OF SYSTEMS OF, and yet the books are wildly different in content and style. How does the idea of systems, either metaphorically or literally, play a role in your work? Why do you think I chose this moniker?

It’s a perfect fit for my work. My poems want to systematize relentlessly. They’re not systems, but they’re “of systems” and then they’re reaching out for something else “of” something else that we never get. The stretch in which the series title is paused, mid-action, feels a lot like what my work wants to do.

Speaking of monikers, what does your title represent? How was it generated? Talk about the way you titled the book, and how your process of naming (poems, sections, etc) influences you and/or colors your work specifically.

I made a list of titles pulled from lines in these poems and other poems and sat with them, showed them to friends (actually primarily to Emma Steinkraus, who made the covers of the books in the series). In the University of Iowa Natural History Museum, there’s a 1900 vintage cyclorama of a wildlife habitat. I feel like the book is a model that’s designed to represent some kind of seen and felt reality of space, but also to distort it. I liked the idea of something that feels like a real representation and like a not real one at once.

[line]

What does this particular collection of poems represent to you…

It represents a first real attempt at making a model city out of poems, and of trying, in a sustained way, to build a context where the shifty totalizing of being a person with a private world is part of being exposed to the sensory data of a city with all of its moving parts. It feels like a model plane. Like a book of sketches.

…as indicative of your method/creative practice?

It represents working and continuing to work, and setting my work into exchange with other folks thinking about what poems might do.

…as indicative of your history?

I grew up in Philadelphia and was hugely excited by trains and subway depots and fire trucks and campus safety officers on bicycles and times of day when train stations or intersections or libraries were really busy and times of day when no one was there. In many ways, cyclorama is just a documentation of a childhood enthusiasm for infrastructure and how it works and moves.

…as indicative/representative of your political or social beliefs?

The poems in cyclorama are interested in what kinds of participation are possible in the public sphere, and what kinds of fear or excitement motivates or makes possible different modes of participation for different folks. For whom is the public sphere public? Who has the power to change the kinds of participation that are possible for different people and groups at different times?

…as indicative of your mission/intentions/hopes/plans?

These are poems. My hope is to keep writing poems.

[line]

What formal structures or other constrictive practices (if any) do you use in the creation of your work? Have certain teachers or instructive environments, or readings/writings of other creative people (poets or others) informed the way you work/write?

I’m interested in speed, in writing speedy poems, and so I’m often condensing my natural impulses of what a line is and how it can move. Sophie, in her work, is super invested in listening to poems, in using the soundscape of a poem to direct its movement, and the way she does that changed how I attend to what my own poems want to do. She’ll remind me that I was interested in writing soundy poems before, but I listen differently now.

Two poets I’m thinking about in this moment (and in many moments) who model movement through space done by private humans in a way that’s eternally stunning to me are Leslie Scalapino and Nathaniel Mackey. [Ed: Davy contributed this piece on Mackey for the 3rd Annual NAPOMO 30/30/30 for The OS in 2014]. Also, last fall I taught Rachel Levitsky’s Neighbor and my students were all taken with how it moves and thinks, and that’s a book I go back to often to think about how it considers what it means to live in a city in proximity to other folks doing the same (and different) things.

[line][line]

[articlequote] I think my role, and maybe everyone’s role, is to keep participating. To show up at readings. To keep writing. To tell someone when you love their work and why you love it. Beyond: I don’t know. It’s important to me to help folks in my life who are scared of poems to find a way in, to figure out a mode of thinking about poems (or just one poem) that’s exciting or interesting to them. Sometimes that happens in the classroom. Sometimes in other places. I went with my mom to her knitting group in April and spent a long time talking to one woman about why she found poems scary, and why she found them exciting. That was a pleasure.[/articlequote]

[line][line]

Let’s talk a little bit about the role of poetics and creative community in social activism, in particular in what I call “Civil Rights 2.0,” which has remained immediately present all around us in the time leading up to this series’ publication. I’d be curious to hear some thoughts on the challenges we face in speaking and publishing across lines of race, age, privilege, social/cultural background, and sexuality within the community, vs. the dangers of remaining and producing in isolated “silos.”

My experiences with other poets, both ones I know and ones I don’t, have been an odd mixing of isolated spaces. Some of it is aesthetic. Some of it is geographic. Some of it is demographic. Some of it is dispositional. Most of the ways I know how to talk about poetry are either comparative or exclusive, or both, and the space between talking about a poem and talking about the body that made it is slippery to me. Poets seem to be more or less embodied by their readers in different conversations at different moments. I feel like I learn the most about who is writing what from the people I love who are poets, just by talking to them. There’s too much to know about all of it. My personal challenge is to make as much space in my brain and my life as I can to listen attentively to what other people in my life are thinking about, and to share what I know and encounter with them. The poets I’ve met are often really good at exchange – at helping one another think in new ways and about different approaches to poems and everything else. The work I read all feels like it asks for attentiveness. My challenge is to do right by the work I encounter, as well as I can.

[line][line]

Praise for Cyclorama:

[articlequote]Davy Knittle’s poems invite us into a myriad of homes—the house of the body, the street, the car, the subway, the animal. by calling this gem of a collection a “cyclorama,” he invites us into a gorgeous panorama that envelopes us in “the life of every sound,” “the lot for cars between cars,” “dream coffee,” and “in the balance/and behind the balance range.” these poems are paintings. these poems are windows. these poems use language as a process in which motion and relationship are always present” (Rukeyser, The Life of Poetry). Davy’s poems build a world i want to live in—honest, lyrical, smart, unafraid to risk and feel, poems that ask all the hard questions all the right ways. He writes: ‘I do the work/to hold a body/different readers know/is theirs to name.'” – erica kaufman[/article quote]

[line]

[articlequote]”Time and space aren’t really like that — how you expect them to be, at least, not after you start to accumulate so many things to remember. Davy knows that the time and space we really move through, comes from the heart out, always changing. So sometimes you’re arches and a house, sometimes you’re more in the car than other times. He writes “where else is left/ there we can/ spend one night/ in a room/ with nothing/ but the Bangles.” It’s this constant shifting or slipping, not forwards or backwards like a regular car, but inside and outside, in and out. These poems make me feel like I’m in the passenger seat of a very strange car Davy is driving, down real streets, then imagined Houston streets, then dream streets to ER coffee, to feet pounding yellow shirt summer streets, and all around there’s so much activity and possibility, and inside the car, which is the heart of the poems, like inside my heart when I read Davy’s amazing poems, there’s so much life & music & room.” – Laura Henriksen [/articlequote]

[line]

[box]

Davy Knittle’s work has appeared recently or is forthcoming in Rain Taxi, Denver Quarterly, and Caketrain. He lives in Iowa City, where he co-curates the Human Body Series with Sophia Dahlin.

Davy Knittle’s work has appeared recently or is forthcoming in Rain Taxi, Denver Quarterly, and Caketrain. He lives in Iowa City, where he co-curates the Human Body Series with Sophia Dahlin.

[/box]

[line]

[recent_post_thumbs border=”yes”]