[re:con]versations :: OF SYSTEMS OF :: digging deeper with SCHEMA's Anurak Saelaow

[line]

[box]

[quote]In April 2015, The Operating System’s 3rd Annual 4-Chapbook Series, OF SYSTEMS OF, appeared on the scene. A strikingly beautiful set, featuring original art created for the series by Emma Steinkraus, these slim volumes in fact contain multitudes — and their diverse, stylistically varied voices represent four new, decidedly distinct entries into the seemingly ever expanding landscape of young poets publishing today.

In celebration and anticipation of our launch reading this week at VON I wanted to dig deeper with these poets, giving them an opportunity to engage in process dialogue about these texts and their creative practice, and giving you the opportunity to break right through that fourth wall.

I stole a line (which is to say, I recycled some of my own questions) from an interview I did with poet JP Howard, which appears in SAY/MIRROR — and extrapolated from there in speaking to each of these poets, teasing out answers as different as the poets themselves.

Please consider this template, approaching The OS’s key concerns of personal and professional practice/process analysis combined with questions of social and cultural responsibility, as an Open Source document — questions to ask yourselves or others about process and the role of poetry today.

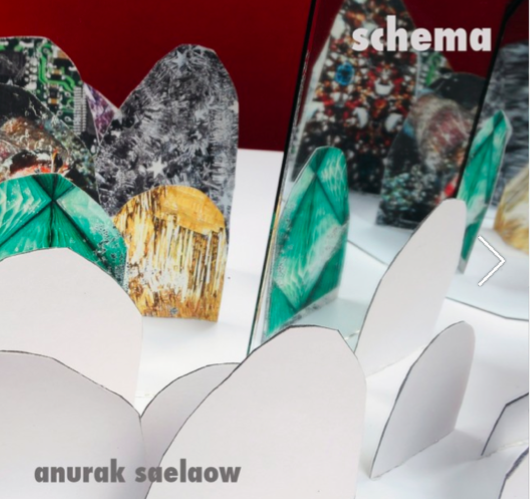

In this conversation, I talk to Anurak Saelaow about his work and his debut chapbook on The OS Press, Schema.

Series Editor / OS Managing Editor Lynne DeSilva-Johnson [/quote]

[/box]

[line][line]

[articlequote]In a sense, my chapbook is a blueprint for a state of mind, a map to the weird Freudian subconscious that birthed it. This is reflected both in terms of the immediacy of the thought process that underscores several pieces (as Brenda Iijima puts it, “the historical moment”) as well as the kind of subterranean or claustrophobic environments that form the setting. – Anurak Saelaow [/articlequote]

[line][line]

Who are you?

A student, a Singaporean, a poet – the labels come and go. Right now? Someone utterly feeling unqualified to be doing a Q&A like this.

Why are you a poet?

A little cliché, I know, but everyone has a creative urge of some kind. I like to joke that I write poetry because I lack the patience for prose.

When did you decide you were a poet (and/or: do you feel comfortable calling yourself a poet, what other titles or affiliations do you prefer/feel are more accurate)?

I was fourteen when I started dabbling in poetry, encouraged by a circle of friends in the Singaporean equivalent of high school. In retrospect, I’m not sure I deserve the title even today – working towards that is a lifelong process of writing, revising, and revisiting.

What’s a “poet”, anyway?

To me, someone with the ability to frame the world with a certain flair and condense it into the span of a poem. I like to think of that Dickinson line – “Tell all the truth but tell it slant”.

[line]

What is the role of the poet today?

The same as it’s always been – to clarify and transcribe his or her experience and tame it into verse. Then again, given the ever-increasingly-experimental nature of post-modern work today, we may have to keep seeking new definitions for “experience” and “verse”.

What do you see as your cultural and social role (in the poetry community and beyond)?

It’s intimidating to think about any of my work having any larger consequences for society as a whole. I guess that a fundamental part of growing up is realizing that we don’t write in a vacuum, but in a place that takes note of and responds to your thoughts and actions. Obviously I still have a long way to go before I can achieve the kind of stature required to really rattle society – but part of my maturing as a poet is reaching out and grasping this sort of responsibility, I suppose.

[line]

Talk about the process or instinct to move these poems (or your work in general) as independent entities into a body of work. How and why did this happen? Have you had this intention for a while? What encouraged and/or confounded this (or a book, in general) coming together? Was it a struggle?

Schema fell into place in my two years of military service, although some of the earlier pieces were written in my last year of high school. It was a work-in-progress for quite a while, having been interrupted by the rhythms and demands of life in uniform.

The chapbook follows a certain kind of narrative arc which was undoubtedly influenced by real-life events – these, of course, had to take please before I could meditate upon them and come to the conclusions that I did. Writing it all down in verse was an opportunity to both agonize over and clarify my understanding of everything that happened, with the construction of the poems happening at the same time as the construction of my interpretations.

Did you envision this collection as a collection or understand your process as writing specifically around a theme while the poems themselves were being written? How or how not?

The overall conceit of the human mind being a hermeneutic machine processing the world is certainly not unique to me. However, it’s an idea which has definitely framed my worldview for quite some time, and I was able to put pressure on the implications of this through my writing. After all, there are depressingly lonely ramifications for such a solipsistic framework of mind.

This conceit formed a theme around which the collection was organized, with many recurring resonances and images that occurred pretty naturally. Most of the pieces fell into a spectrum, the narrative timeline, although I did feel the need to write some poems to bridge the gaps.

The four chapbook collection lives under the umbrella OF SYSTEMS OF, and yet the books are wildly different in content and style. How does the idea of systems, either metaphorically or literally, play a role in your work? Why do you think I chose this moniker?

Well, a machine is a self-contained system – and the mind is just a sophisticated machine.

In a sense, my chapbook is a blueprint for a state of mind, a map to the weird Freudian subconscious that birthed it. This is reflected both in terms of the immediacy of the thought process that underscores several pieces (as Brenda Iijima puts it, “the historical moment”) as well as the kind of subterranean or claustrophobic environments that form the setting.

Speaking of monikers, what does your title represent? How was it generated? Talk about the way you titled the book, and how your process of naming (poems, sections, etc) influences you and/or colors your work specifically.

What I love about the word “Schema” is its various nuances across so many different disciplines. In psychology, it’s a system or paradigm of thought, while for engineers and computer scientists it refers to a schematic or a blueprint for a machine or a file system. (Correct me if I’m wrong, please – I certainly cannot profess to any great expertise in any of these fields.)

The rigid structure (5 sections of 5 poems each) is also an attempt at discipline. My sections were named and themed around an overall narrative arc – not an explicit journey, but a meditative train of thought. The great Joe Fasano, one of my instructors for a poetry class this semester, talked at length about the role of the ur-myth in structuring longer works of poetry – in retrospect, this seems like the exact motivation behind my work: descent, entrapment and obsession, and an eventual return to light.

[line][line]

[articlequote]There is always a fine balance between speaking up for a marginalized community and co-opting their voices. I don’t think that being a poet grants anyone any special sort of authority, and to speak on behalf of the marginalized runs the risk of unnecessarily and inauthentically inserting yourself into a dialogue in which you may not necessarily have a place.

Then again, this doesn’t mean that advocacy has no place in poetry. Poetry is unique to the individual in the sense that it is the conveyance of experience and a particular mindset – and it is this very act of conveyance that imbues poetry with the potential to influence and generate change. – Anurak Saelaow[/articlequote]

[line][line]

What does this particular collection of poems represent to you

…as indicative of your method/creative practice?

A year on from Schema’s acceptance by The Operating System, I think that Schema marks a milestone in my transition from juvenilia to finding the right voice. It encapsulates the last traces of the whiny adolescent Anurak, and perhaps a seed of whatever comes next.

That being said, I’m certain my work has changed in the year that I’ve entered Columbia. Under the instruction of great, great teachers such as Dorothea Lasky and Joe Fasano, I’ve been exposed to more paradigms of verse and thought than ever before, and I’m excited to see what my new efforts might bring to light.

…as indicative of your history?

Schema is at once personal and not personal – it’s sort of like those Hollywood films that claim to be inspired by a true story. Like I mentioned above, its writing helped to paint over and clarify a turning point in my life, allowing me to make sense of what was nebulous and unstructured.

…as indicative/representative of your political or social beliefs?

Schema is somewhat apolitical – I don’t think I have an overt social message. Then again, political and social beliefs might be said to stem from more fundamental urges that run through the mind – impulses towards safety and security, the need for companionship and love, what is proper and what is vulgar. Building on Marslow’s hierarchy, we might construe political views as the sum or the symptom of all the baser impulses that come before these social beliefs. (That’s a cop-out answer, I know, I’m sorry.)

…as indicative of your mission/intentions/hopes/plans?

I think that what I’ve explored in Schema may prove to be a lifelong obsession. The questions of desire and of the mind can’t be explained away in the span of twenty-five poems. and I think I’ve barely scratched the surface. Then again, maybe I’ll find some other muse to follow.

[line]

What formal structures or other constrictive practices (if any) do you use in the creation of your work? Have certain teachers or instructive environments, or readings/writings of other creative people (poets or others) informed the way you work/write?

On the level of form, I found that my writing at the time fell naturally into the cadences of the two-line stanzas which form the mechanical heart of the chapbook. I didn’t need to radically re-organize any of the pieces to fit this form, which made the whole collection a little more seamless.

I had a friend tell me that the two-line stanzas formed a “false couplet” of sorts, which certainly had poetic undertones. Sometimes I tried to use unnatural or forced enjambments to elicit discomfort and awkwardness, although I’m not too sure if I succeeded.

Let’s talk a little bit about the role of poetics and creative community in social activism, in particular in what I call “Civil Rights 2.0,” which has remained immediately present all around us in the time leading up to this series’ publication. I’d be curious to hear some thoughts on the challenges we face in speaking and publishing across lines of race, age, privilege, social/cultural background, and sexuality within the community, vs. the dangers of remaining and producing in isolated “silos.”

There is always a fine balance between speaking up for a marginalized community and co-opting their voices. I don’t think that being a poet grants anyone any special sort of authority, and to speak on behalf of the marginalized runs the risk of unnecessarily and inauthentically inserting yourself into a dialogue in which you may not necessarily have a place.

Then again, this doesn’t mean that advocacy has no place in poetry. Poetry is unique to the individual in the sense that it is the conveyance of experience and a particular mindset – and it is this very act of conveyance that imbues poetry with the potential to influence and generate change. I don’t see it in terms of happy-clappy slam poetry with overt and clear motives, but rather through the lens of curating a specific experience.

Poetry’s origins as an oral tradition also means that there is definitely a communal aspect to the process as well. I’ve felt the tension between authenticity and the poetic self when workshopping with other poets – if someone says something one way in a poem, who am I to tell them that this other way is a better way to frame their struggle? I didn’t live their lives, I don’t know if that’s how they thought.

[line]

Praise for Schema:

“Schema is a book that gravitates toward the shimmering heat of the historical moment. This book accentuates the nerve center of pathos, the hardwiring of passion. Anurak Saelaow refocuses the pace and pulse on what is happening in the now, with dramatic results. This is a dynamite work that doesn’t rest. The jolt will recalibrate you.” – Brenda Iijima

[line] [box]

Anurak Saelaow is a Singaporean undergraduate at Columbia University. Previously, his work has appeared in print and online, in journals such as the Quarterly Literary Review Singapore and Ceriph Magazine. He is currently a staff editor at Quarto Magazine. [/box]

[line]

[recent_post_thumbs border=”yes”]