FIELD NOTES :: No Instructions for Assembly :: Kameelah Rasheed's Photographic Memory

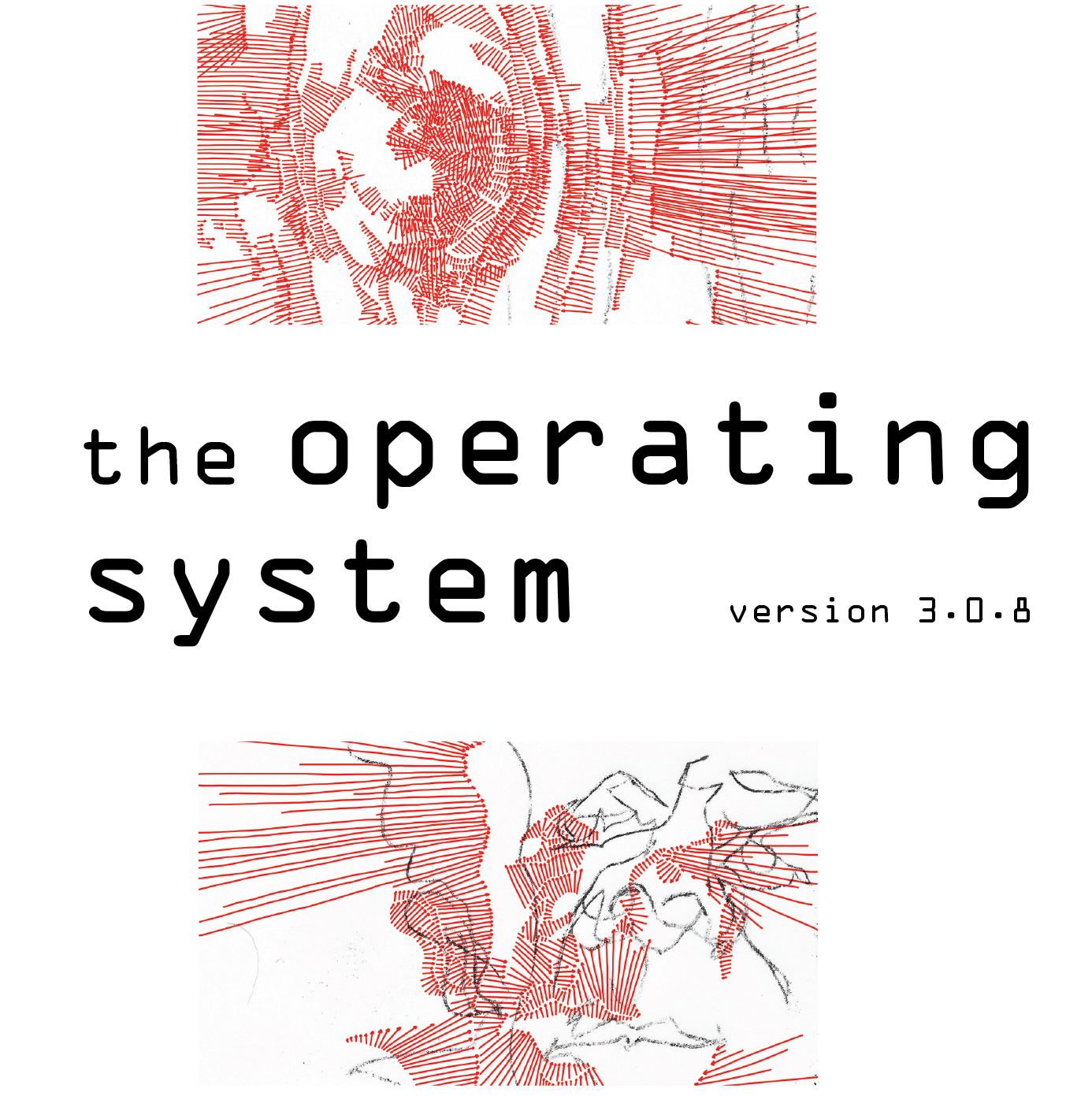

While an Artist in Residence at the Center for Photography at Woodstock this summer, I continued to work on the series Memories: No Instructions for Assembly. This series which has morphed into six evolving iterations – I, II, III, IV, V, and VI is born from my family’s experience with displacement and loss. There is limited photographic evidence that my family ever existed. Photographs were lost when we were unlawfully removed from our home in 1998. Some photographs were water-damaged or accidentally trashed before we packed seven lives and accompanying articles into a burgundy station wagon and made our home in a 450-square foot illegal attachment where my grandfather died, alone, nine years prior of stomach cancer. An attempt to conjure my family back into existence, in Memories: No Instructions for Assembly, I weave together orphaned photographs found at garage sales, photos stolen from the Facebook pages of estranged family members, magazine pages, water-damaged images salvaged during my family’s 10-year bout with homelessness, and original photography to re-imagine a lost family history. Working in the tradition of the archaeologist and the archivist, I sample as well as reorganize existing materials into a series of images to produce a non-linear narrative that dances between vivid and vague memories.

From Nietzsche’s Human, All-Too-Human (and I’m grateful to David Shenk’s excellent book The Genius in All of Us for bringing these remarks to my attention). Nietzsche writes:

From Nietzsche’s Human, All-Too-Human (and I’m grateful to David Shenk’s excellent book The Genius in All of Us for bringing these remarks to my attention). Nietzsche writes:

Artists have a vested interest in our believing in the flash of revelation, the so-called inspiration…[shining] down from heavens as a ray of grace. In reality, the imagination of the good artist or thinker produces continuously good, mediocre, and bad things, but his judgment, trained and sharpened to a fine point, rejects, selects, connects… All great artists and thinkers [are] great workers, indefatigable not only in inventing, but also in rejecting, sifting, transforming, ordering. [Shenk, p. 48]

There is a lot of wisdom in those remarks, beginning with the fact that Nietzsche draws a firm connection between good artists and good thinkers. Both rely on a combination of imagination and rigor to arrive at their final destination (the Nobel Prize-winning immunologist Peter Medawar similarly spoke of the balance between imagination and critical thinking as being essential to good science).

My artistic practice borrows from the literary tradition of poet Harryette Mullen. In the introduction of Harryette Mullen’s Recyclopedia:

Trimmings, S*PeRM**K*T, and Muse & Drudge (2006), Mullen writes,

Trimmings, S*PeRM**K*T, and Muse & Drudge (2006), Mullen writes,

[i]f the encyclopedia collects general knowledge, the recyclopedia salvages and finds imaginative uses for knowledge. That’s what poetry does when it remakes and renews words, images, and ideas, transforming surplus cultural information into something unexpected.

Likewise, my work seeks to make use of surplus cultural information to conjure up new narrative possibilities and to craft unexpected relationships between textual and visual data. Central to my artistic practice is the accumulation of disparate visual and textual data from estate sales, digitized portals, public libraries, and family collections. Using data ranging from excerpts of apocryphal texts to popular historical images to family wedding images, I work to create simple images that articulate endless permutations and possibilities. This work lives in the realm of the revelatory rather than the didactic or polemic. While at times self-referential and hermetic, these final pieces function as indexical links to larger personal and social histories and imagined spaces. I am interested in how seemingly disparate images and text create their own logic and grammar—an internal language that invites the audience into an intimate space.

In early 2012, she was selected as an Artist-in-Residence at The Center for Photography at Woodstock in upstate New York. In late 2012, she was named a recipient of the Real Art Ways STEP UP Award, an honor that includes a solo exhibit slated for July 2013, a publication, and an artist talk.

She has exhibited in numerous shows in New York City and Brooklyn, NY; Oakland, CA; San Francisco, CA; Washington, D.C.; and Johannesburg, South Africa. Her work has been published in a variety of publications including Harvard University’s critically acclaimed Transition Magazine, SF Moma blog, Hyperallergic, ITCH

Kameelah’s writing has appeared in The Nation (online edition), Well & Often Press Reader, Pambazuka: Pan African Voices for Freedom and Justice, Wiretap Magazine, Make/Shift Magazine, Blacklooks, Specter Literary Magazine,Liberator Magazine, and Restorative Justice. Her essay “Lines of Bad Grammar” was included in the book I Speak for Myself: American Women on Being Muslim

Kameelah is also the co-founder and curator of Mambu Badu, a photography collective for women photographers of African descent. Additionally, she is a Senior Editor (Interviews and Photography) at Specter Literary Magazine.

She is entering her fifth year of high school teaching as a founding teacher specializing in the needs of recent dropouts and court involved youth.

In her free time, she enjoys volunteering with the New York State Special Olympics.